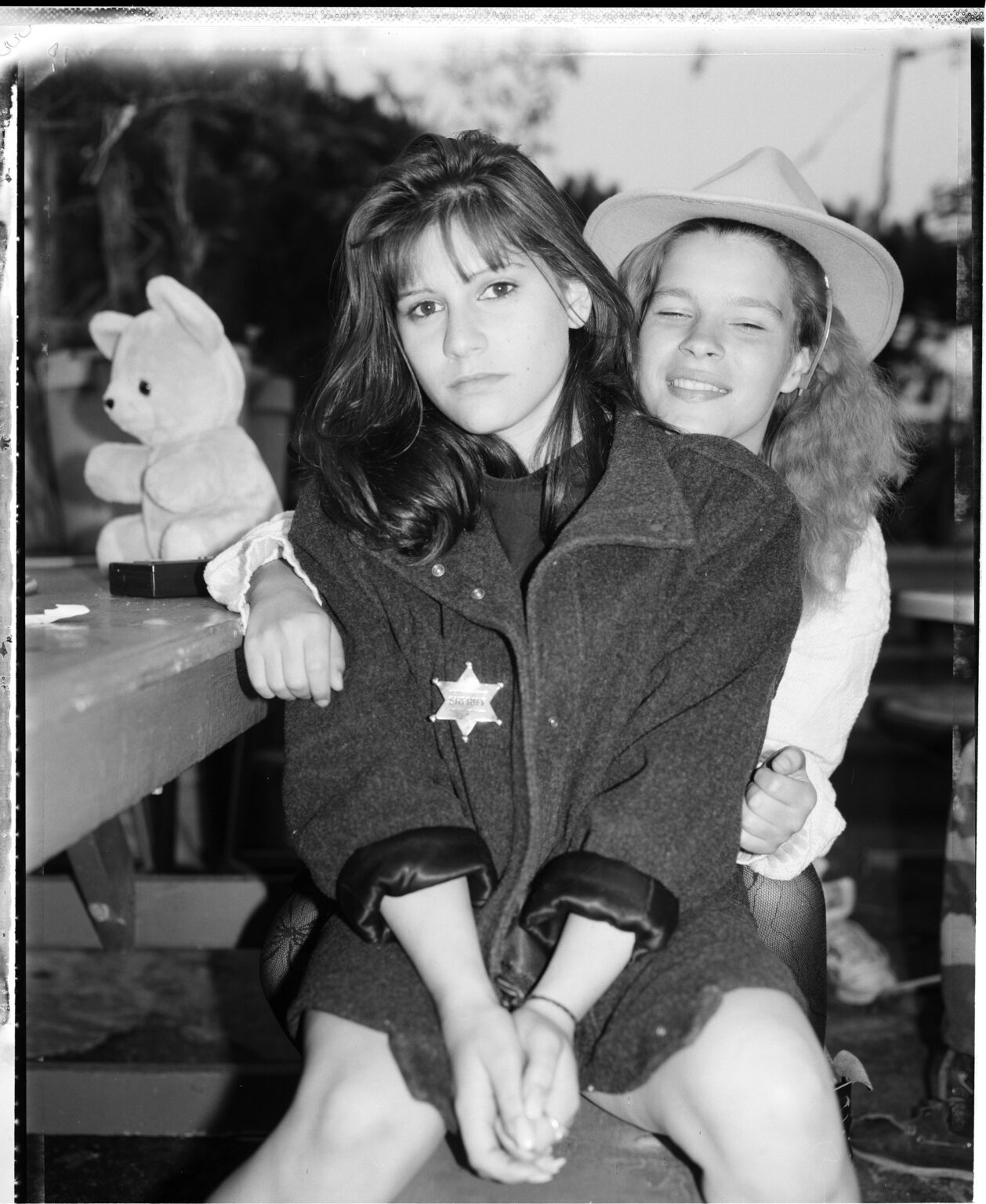

Among all the endless and rich possibilities of photographic storytelling, there are few projects that have risen to match the depth and poeticism of Magnum photographer Jim Goldberg’s iconic body of work, Raised by Wolves.

Supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship, Goldberg began Raised by Wolves in the mid 80s and spent a decade photographing the lives of homeless youths in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Beginning by entering into communities of kids living in the streets, Goldberg forged close relationships with his subjects, making friends and intertwining himself into their lives. Such a commitment goes beyond the simple act of image-making, and enters into a far rarer integration between subject and author that Goldberg forged to unlock depths of intimacy rarely found in pictures alone.

Fellowship interviews Jim Goldberg

To start, Jim, can you just talk a bit about your background as a photographer and the journey your career has taken you on? And are there particular photographers or inspirations that have shaped your approach to image-making?

In my early twenties I travelled to Thailand, where I lived in a monastery, thinking at the time that I would become a buddhist monk. Perhaps if I had had more discipline I would have succeeded, but as it was, I became a photographer instead. This time away allowed me to reflect on the potential to use my way of seeing to engage and build connections with the people I encountered.

In the late seventies I moved to San Francisco. It was there I studied with Larry Sultan, and later on worked with Robert Frank- they both had a huge impact- as my mentors and my friends for many years. Their practices heavily shaped my image-making and thinking. Soon after graduate school, I had a show at MOMA_NY of my Rich and Poor work alongside Joel Sternfeld and Robert Adams.

To be honest, the most important influence on my work has been the people I have met and worked with. Through social practice and various other (organic?) ways of working, the relationships feel symbiotic with the people whom I photograph.

Jim Goldberg

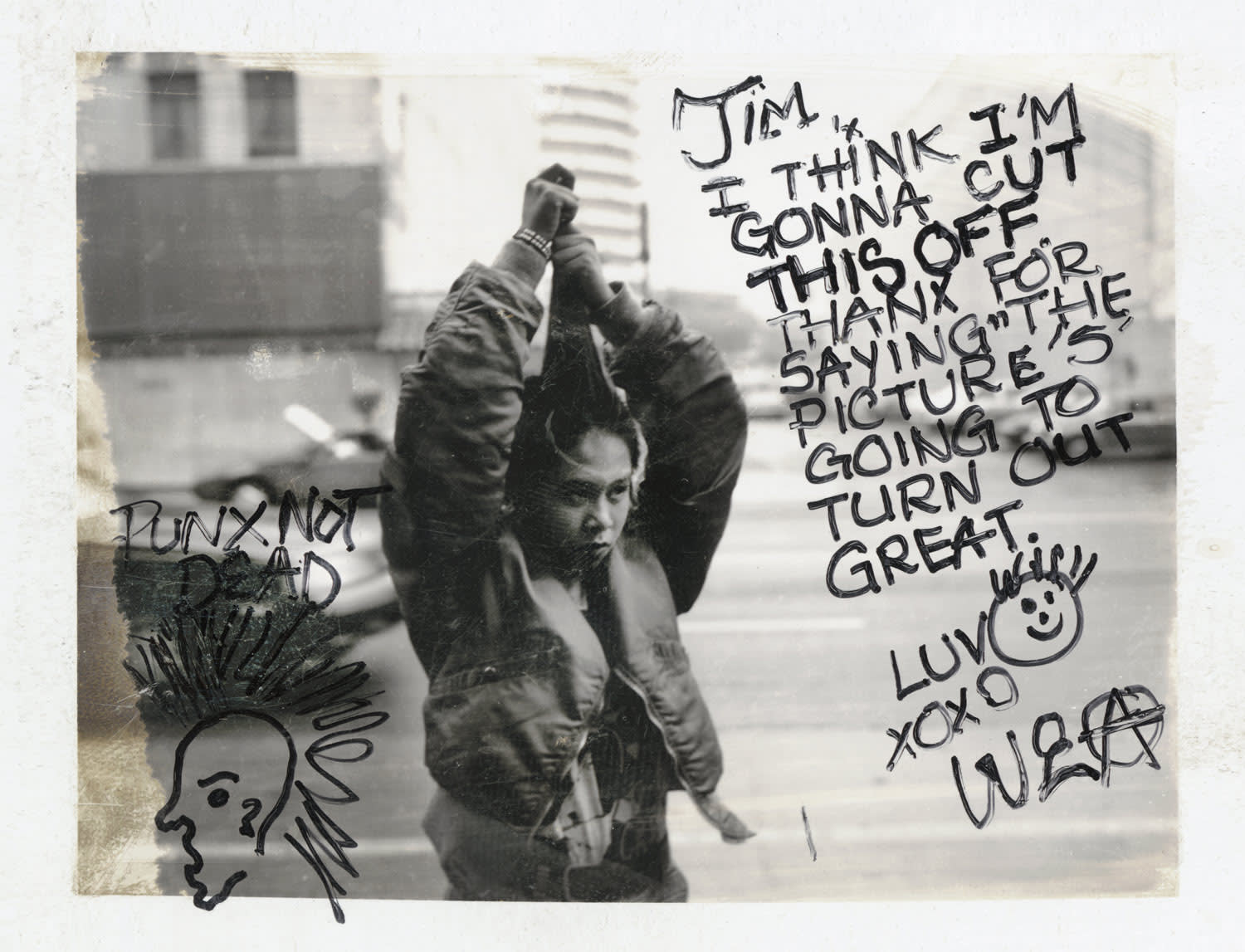

Street Map #8, Untitled, 1987 from Raised by Wolves

© Jim Goldberg

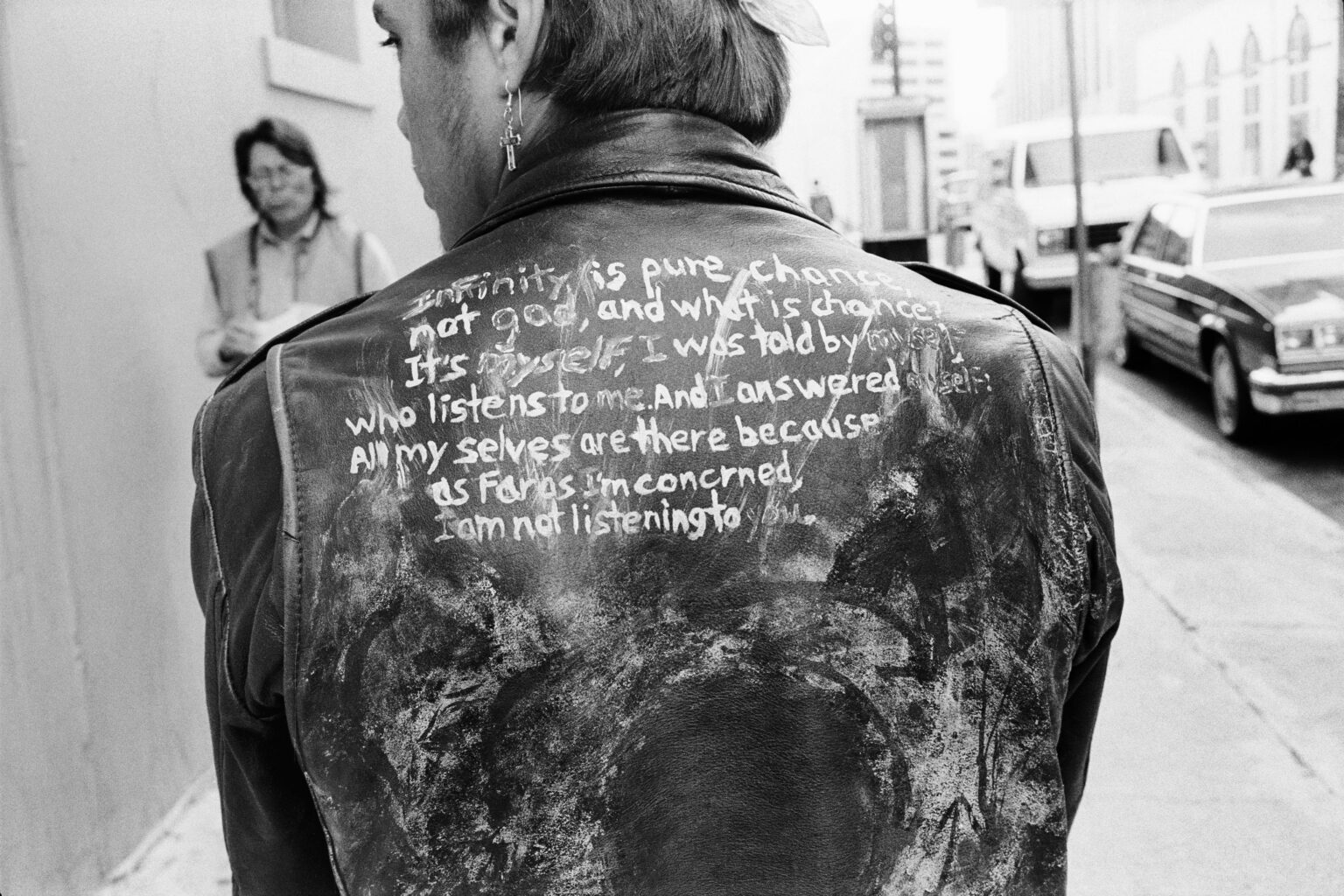

There was a negative reaction from some critics in the photo community, to my combining text with images, but to me it signaled that I had disrupted something. One critic referred to my work as “a betrayel of photography”.

To be honest, the most important influence on my work has been the people I have met and worked with. Through social practice and various other (organic?) ways of working, the relationships feel symbiotic with the people whom I photograph.

Fairly late in my career I joined Magnum and was introduced to an extensive network of talented photographers who are very different from myself and who expanded the way I approached and thought of photography.

I hope this answered your question. There are just too many people across various mediums who have influenced my approach to image-making to name just a few (seems inadequate) . I constantly look at studio practice, social practice, painting and film as much as I do photography. I’ve also been heavily influenced by my time in California- different artists and movements that have come out of the state over the last 50 years.

When did you begin your project Raised by Wolves, and did you know at the beginning of your image-making what you wanted the project to be?

I began Raised by Wolves in the mid 1980’s. At the time I had recently finished a series called Nursing Home, in which I had spent a year in an assisted living facility located in Cambridge, Massachusetts working with the elderly. In 1985 I received a Guggenheim Fellowship and I knew I wanted to use this opportunity to work with young people at risk. Having lived in San Francisco for a few years, the epidemic of homeless youths had been on my mind for awhile – the amount of kids living on the curb right outside my door led me to the streets of San Francisco and Los Angeles. Despite photographing throughout the 80’s, it wasn’t until October 19, 1991, when I began to work with Philip Brookman to create the book and later a traveling multimedia exhibition. Up until that time I had been collecting images, stories, drawings, writing, ephemera, film and video, anything that seemed relevant to conveying these stories.

© Jim Goldberg

How did the project evolve over the course of your shooting it?

I spent the first two years of the project hanging around communities of kids who lived on the streets, working with youth agencies and street preachers. In those years all I was doing was immersing myself in their lives, making friends, and mapping the land. I began photographing more as I grew closer with a few of the kids, including Echo and Tweeky Dave. For many years I wasn’t sure what Raised by Wolves would become, but my intuition told me that ultimately it would become a book.

And then, as I said, I began to work with Philip Brookman in the fall of 1991 editing and organizing all the work I had made, and that’s when the book began to take shape. Throughout the 4-year process I made eight different maquettes. Recently I worked with Stanley Barker to publish a book called Fingerprint, which consisted of stack unseen reproduced polaroids from the series.

Do you know what became of Tweeky Dave and Echo, the two subjects in the center of Raised by Wolves?

As told in the book, Tweeky Dave never left the streets for any substantial amount of time. At one point he went to live with a family in San Diego, but he hated the structures that were expected of him.

He quickly returned to Hollywood Boulevard, and at some point his body gave out, from the stressors of homelessness, malnutrition, and drug use. When he was sick in the hospital I reached out to his parents, who turned out to be a devout Christian couple living in Texas. They refused to acknowledge him or his situation. At that point I became Dave’s sole guardian and after he passed away I was entrusted with his ashes. I organized a funeral service for him on Hollywood Boulevard where his community could say goodbye.

Echo’s trajectory is also included in the ending of the book. Her mom travelled to San Francisco for the birth of Echo’s first child, and after that Echo returned to the East Coast to live with her mother for a time. We’re still in touch. In 2020 we did a small sale of RBW Bootleg, with all of the proceeds donated to Beth (Echo) for support during the pandemic. She currently has four children, lives in New Jersey, and struggles and thrives like the rest of us.

© Jim Goldberg

You consider Raised by Wolves as part of a trilogy, which includes two other projects, Rich and Poor, and Candy. Can you talk about how these three projects overlap, and how they differ?

The trilogy refers to the different stages of my development and practice. I grew up in a working-class family in New Haven, Connecticut – my dad owned a candy store – at a time when the town was famous for these giant anti-poverty and urban renewal measures, which all quickly went downhill and caused more poverty and community destruction than to begin with. This was the reason I was in tune with the gap between the haves and have nots with respect to wealth and poverty when I got to San Francisco. The city has its own class divides, and that was in my mind when I made Rich and Poor. Raised By Wolves came from a mix of things. It was the experience of moving to California and seeing homelessness out my front door, as well as my own teenage years involving different degrees of my running away from home. I related to the kids I met and photographed, all of whom left home for a better life with hopes of starting over far from where they grew up. My project Candy was a return to the beginning – with me revisiting and making an examination of my hometown New Haven, CT.

In many ways I think of the book as a film. It begins with a fade in, positioning the audience as voyeurs to a suburban home through binoculars and quickly immersing them in the larger story of these kids’ lives.

Jim Goldberg

You’ve described the project not as photojournalistic in scope, but existing between “documentary and narrative fiction”. I wonder if you can elaborate on this idea, what it means to you and your storytelling, and how you hope viewers/readers engage with the narratives you’re crafting.

Tank, Room 17, Riviera Hotel, 1987 from Raised by Wolves

© Jim Goldberg

I was born out of a documentary tradition – the idea of “being a witness to the world”. Typically a journalistic take would tell you what to think about a situation as it was presented, however, I’ve always been interested in different sides of a single idea or issue through a variety of approaches. This is why I began to integrate text when making Rich and Poor, because I was interested in representation and the gaps between visual and written language. Later on I employed various strategies including social practice and installation. I hope the variety of mediums challenges my audience to ask questions and to open themselves to new ways of seeing.

The idea of narrative fiction is used for a variety of reasons in Raised By Wolves. Occasionally I changed the subjects names as a way to protect their identities because some were minors, and some were participating in illegal activities, but more often than not, the names were self-fabricated to depict who they wanted to be known as on the streets. Creating a fictive narrative also allowed me to play with incorporating myths in western history, from Romulus and Remus to the repetitive religious/tragic/political stories of children being cast away by their families.

In many ways I think of the book as a film. It begins with a fade in, positioning the audience as voyeurs to a suburban home through binoculars and quickly immersing them in the larger story of these kids’ lives. There is a list of “characters/players,” which alludes to movie credits, or a play/opera programme. As the book progresses, characters are developed as the “plot” builds, along with increasing narrative tension and chapter breaks. These were strategies I felt were compelling ways of telling Echo and Dave’s stories, ways bringing the audience in and getting them to care about them. The book ends with the words ‘fade out’.