When art photographers started digging into the idea of digital photographs as NFTs, a lot of issues that I thought were already solved started emerging again. We used to talk about digital photography as if we had always known what it was and how it works. We got used to the digital image, and perhaps we thought of digital processes as just tools we use to bend reality in new ways. But can a digital file be understood as an actual photograph? Where does the digital photograph exist, how is it viewed? What is a photograph, really?

This discussion on the understanding of photography as a creative act and an art is one that has been happening since the beginning of our medium’s history, and it now seems to be emerging again in a new arena amid the rise of photography NFTs. In this context, we at Fellowship found an opportunity to participate in a revitalized debate about the ways in which our medium communicates as we prepare for yet another of photography’s historical revolutions in the way images are produced, presented, and collected. A basic question that must be answered before we begin understanding photographs as NFTs is: How is it that a line of code can be understood as a photograph?

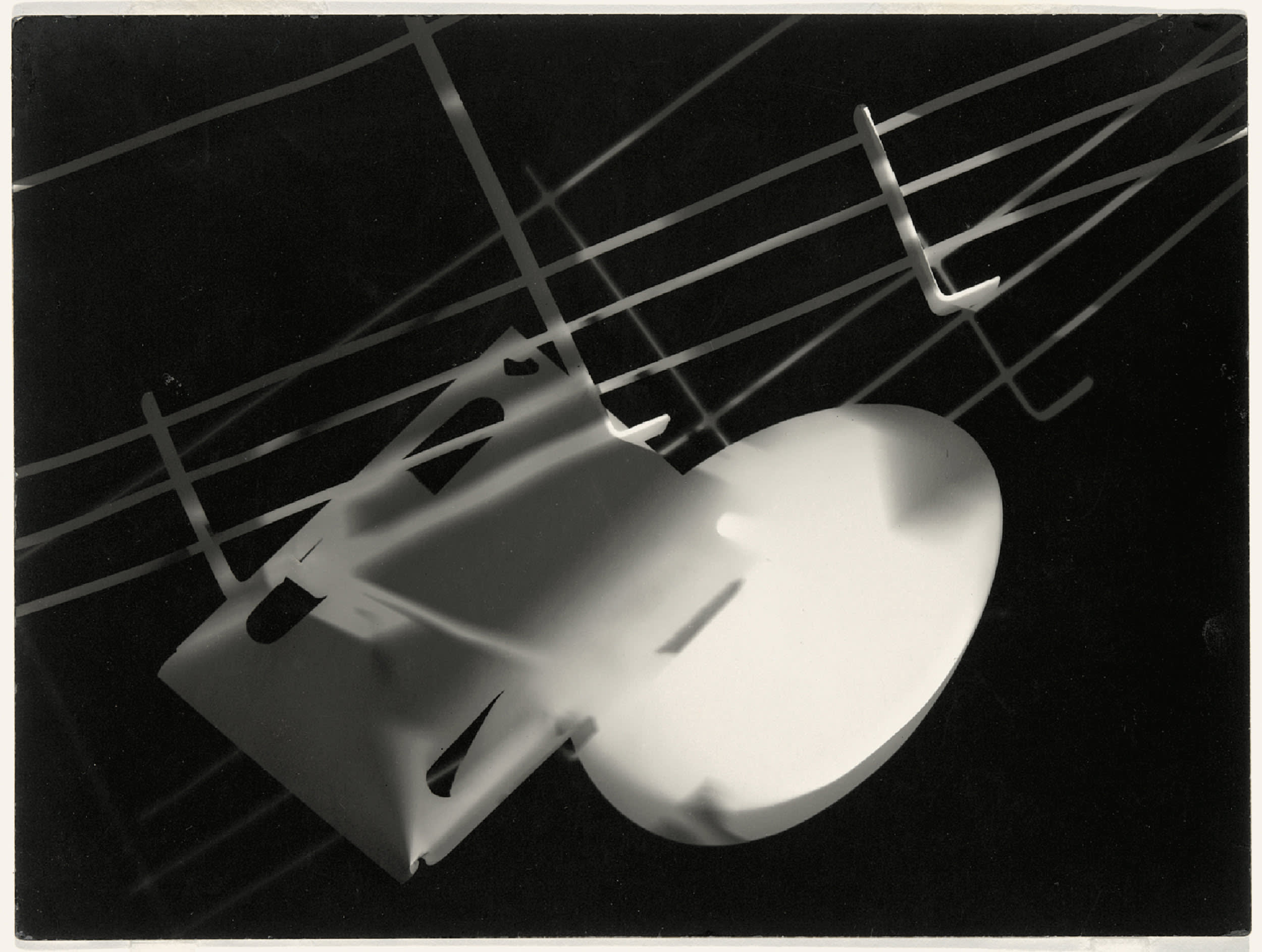

The (im)materiality of photographs

A photograph can be understood as the recording of light into a light-sensitive support. Traditionally we have thought of this as the chemical burning of a light-sensitive material that becomes some kind of analog visual representation of what was photographed. During the digital revolution of the early 2000s, the physical chemicals were replaced by electronic means. I would argue that a block of data, resulting from the interpretation made by a light-sensitive sensor can be understood as a latent image in the same way an undeveloped roll of film can contain one.

This idea calls into question our common understanding of what a photograph is. In art photography, we are used to thinking of a photograph as the object that results from the photographer’s whole process. However, most often what we see is the result the photographer wanted the image to be, not just what was recorded with light, or in other words, what was photographed. This can be said of most photographs we know. Every enlargement of a film negative or positive is a manipulation of a photograph, we could go as far as saying that the decisions made when developing the film are manipulations of the original photograph, a latent image; they are images made by turning the raw record of information into a refined manifestation of the photographer’s vision. The actual original photograph is a latent image that we cannot even see with our naked eyes. We know how a photograph starts, but it is not always certain how a photograph ends.

We sometimes think that prints are perfect for photography just because of their nature, but making a good print is extremely difficult (and expensive)

Fernando Gallegos

For any photograph to be finished and presented, we need an interpretation of the original latent image. This happens in any kind of physical photograph and happens too in digital photography. Every print made of a photograph is an interpretation of an original accumulation of information that we cannot see without external chemical aid. Every digital image (made or scanned) is an accumulation of data that we cannot interpret without technological aid. We sometimes think that prints are perfect for photography just because of their nature, but making a good print is extremely difficult (and expensive). The challenges an artist and printer go through to achieve an output that they can call remotely “accurate” have long existed in both the darkroom and the inkjet studio. A print is not something “natural” for photography, a print is something that’s achieved by an extraordinary amount of work and levels of interpretation from the original latent image. For a long time, the print was the only way of creating a photograph that could be collected. In this nascent era of the NFT, that is no longer the case, and we now turn to the question of the presentation potentials for NFT photographs.

© Mitch Epstein

An NFT works as a non-fungible token of authenticity that unequivocally points to a particular image that is stored and kept in another place such as the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), a decentralized archive system on the internet. What’s important about this is that an artist can now sign a digital file, turning it into an original edition on the blockchain, which can be included in the set of versions that exist for that piece of art. In photography, we usually see a single image reproduced, for example, in an edition of 3 in the size of 100 by 70 cm, and an edition of 5 in the size of 50 by 30 cm, and an edition of 1000 photobooks, etc. Now we can add to that list a digital file backed by the 1 of 1 provenance of an NFT.

Photography is a very flexible medium, one in which we don’t expect the resulting image to be a one-of-a-kind object. Traditionally, photographic scarcity was placed in the trust of provenance based on artist-approved copies (editions) of their work. Provable rarity of photographic prints relied on centralized records that could often prove fallible. On the blockchain, provenance of creation and ownership of a digital image is now not only possible, but logged in an immutable, permanent archive of information that is updated as ownership of the digital object changes hands. Jpegs of course remain infinitely reproducible, but the NFT makes possible the provable ownership of a digital image, a true artist-certified copy.

© Prisca Munkeni Monnier

© Prisca Munkeni Monnier

The challenges of NFT presentation models

Now that NFTs allow the acquisition of original artist-approved pieces of digital art, the question turns to how such works can best be presented for ideal viewing. At this time, the technology for this is limited in very different aspects. Factors such as resolution, size, aspect ratio, dynamic range, contrast, color spaces, etc. make it difficult to have complete control over the way an image is seen. This will obviously push manufacturers to create better ways of displaying digital works of art, not just in displays, but in projections, metaverse environments seen through VR sets, and maybe things we cannot even imagine yet. Does the uncertainty of ideal presentation models create a disadvantage in the viability of NFTs? What will happen with today’s pieces when technology moves forward beyond the specs of a 2022 jpeg?

There are a couple of ways of approaching this concern. One is that the limitations of today’s technology shouldn’t be compared with the future’s possibilities. What we can achieve now with a camera, modern film stocks, modern paper and methods of scanning/printing are completely different from what artists had before. This doesn’t make older prints better or worse, the materiality of older prints becomes a characteristic of those particular pieces of art, they are additional markers of their historical and even social relevance.

What’s at stake with all this discussion is the understanding of the materiality of a digital photograph. Its value is not in how it looks on a particular screen, but in its existence as a digital object with all its faults and all its exciting possibilities.

Fernando Gallegos

Another way of approaching the matter is a philosophical one. As mentioned before, a digital photograph, even the finished photograph, is a data set; one that depends on technological interpretation. It exists beyond what we can see, and when we see a photograph on a screen we are catching just a glimpse of it through the device turned into a window to a digital realm. We can think of screens, projectors, and other forms of displaying digital images as windows to that digital realm; tools that help us interpret the materiality of a digital piece. As technology advances, these windows will be increasingly optimized for the display of digital art.

This brings to the table an issue for all involved; artists, collectors, curators, critics, and the general audience for art at-large. What’s at stake with all this discussion is the understanding of the materiality of a digital photograph. Its value is not in how it looks on a particular screen, but in its existence as a digital object with all its faults and all its exciting possibilities. A screen serves as the primary window that helps us interpret the photograph so that it becomes recognizable to us, but the digital photograph exists beyond any single method of visualization.

© The Guy Bourdin Estate 2023

The value of a hard drive filled with irreplaceable information is found in its invisible code, the very data that makes its function successful. We feel safe using it because we trust there are methods for interpreting the contents, and if the current method fails, we trust we can develop new methods that can translate outdated technology into a current version. As the use of NFTs for digital art becomes more widespread, technological development will always follow; and given the still-nascent nature of NFT adoption in art and the larger cultural sphere, we are just now beginning to realize the long-term potential of how the materiality of artwork on the blockchain can be fully realized.